A/B Test Review: The Impact of Displaying Discount Percentages

“This A/B test was conducted as part of a project within our company’s A/B Testing TF to analyze the impact of displaying discount percentages (%) on the website’s purchase conversion rate and revenue. In the experiment design phase, I used statistical methodologies such as the Chi-squared test, two-proportion z-test, and two-sample t-test to verify differences between the test and control groups. While the discount display did not significantly affect the purchase conversion rate or average revenue per user, the add-to-cart conversion rate showed a notable increase. This revealed that discount information can effectively expedite consumer purchase decisions, and highlighted the importance of developing more effective strategies for communicating product value moving forward.”

| Performance Summary |

|---|

- Add to Cart CVR (Supplementary Metric): p-value = 0.0438 → Significant Increase |

Table of Contents

- STAR Summary

- Situation

- Tasks

- Actions

- Results

All-in-one Jupyter Notebook

1. STAR Summary

Situation

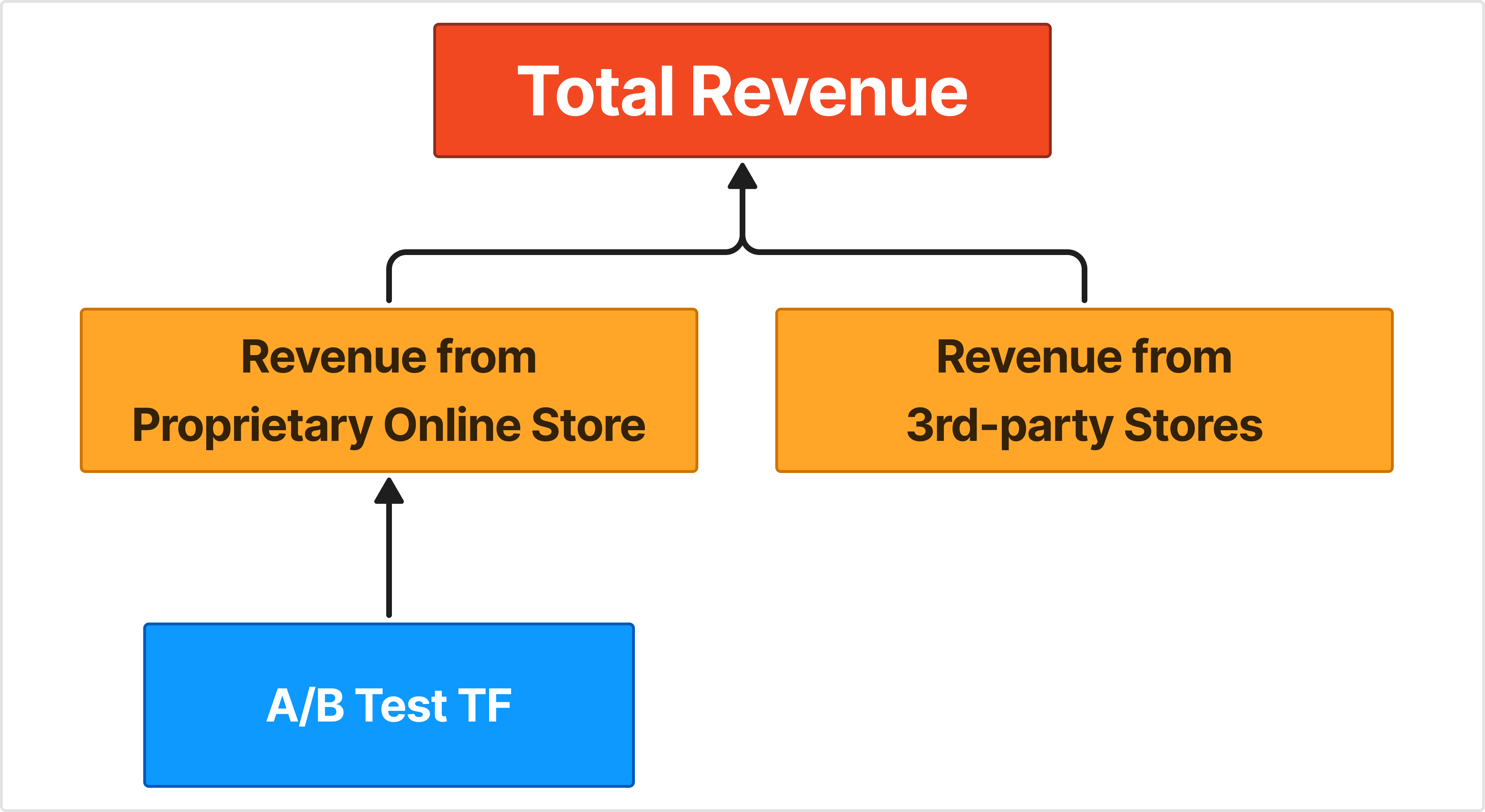

- In 2023, an A/B Test Task Force (TF) was established to enhance the company’s data-driven decision-making process. As the sole data analyst, I led the TF.

- The TF’s goal was to improve purchase conversion rates and revenue on the company’s website, and we conducted around 20 A/B tests.

Tasks

- A product manager suggested that displaying discount percentages (%) on product images could increase conversion rates by leveraging consumer psychology.

- We decided to experiment with displaying discount percentages (%) on product images to see its effect on conversion rates.

Actions

- Key metrics were set as the Purchase CVR and Average Revenue per User (ARPU), supplementary metrics were set as the Add to Cart CVR and Begin Checkout CVR, and the guardrail metric was the rate of users bouncing to other e-commerce platforms.

- We formulated the hypothesis that displaying discount percentages would increase Purchase CVR and ARPU, setting Type 1 Error (α) at 0.05.

- Using chi-squared tests, two-proportion z-tests, and two-sample t-tests, I validated the independence and differences between the test and control groups.

Results

- Conclusion from key metrics: Displaying discount percentages did not bring significant changes to Purchase CVR and ARPU, which may be because it did not effectively communicate the inherent value of the product.

- Increase in Add to Cart CVRT: Discount information acted as a driver for purchase decisions, increasing the Add to Cart CVR, showing that visually highlighting discounts could positively influence user behavior.

2. Situation

- In 2023, an A/B Test Task Force (TF) was established to enhance the company’s data-driven decision-making process. As the sole data analyst, I led the TF.

- The TF’s goal was to improve purchase conversion rates and revenue on the company’s website, and we conducted around 20 A/B tests.

2.1. Formation of the A/B Test TF

Our company, which had been steadily strengthening its data-driven decision-making process, formed an A/B Test Task Force (TF) in 2023. As the only data analyst, I was appointed as the TF lead. The following colleagues joined the TF.

- Executive (CSO)

- Executive (CBO)

- Product Manager

- Product Designer

- Marketer

- Frontend Developer

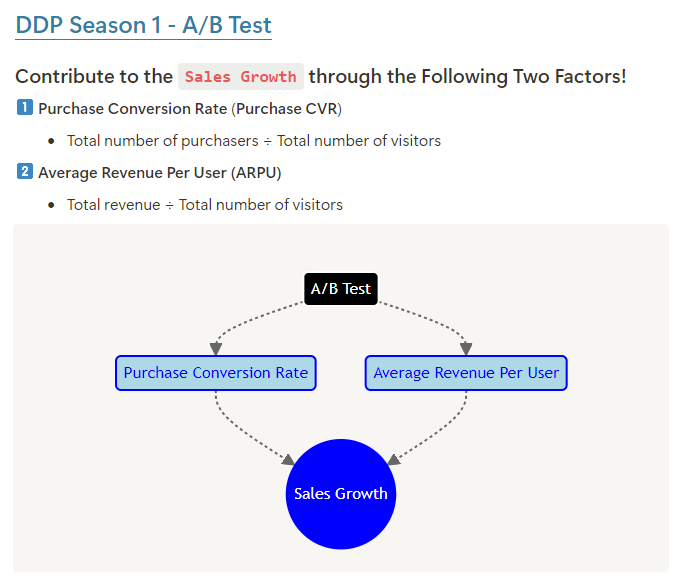

2.2. Goals of the A/B Test TF

The TF’s goal was to improve conversion rates and revenue on the company’s website. To achieve this, we conducted around 20 A/B tests.

3. Tasks

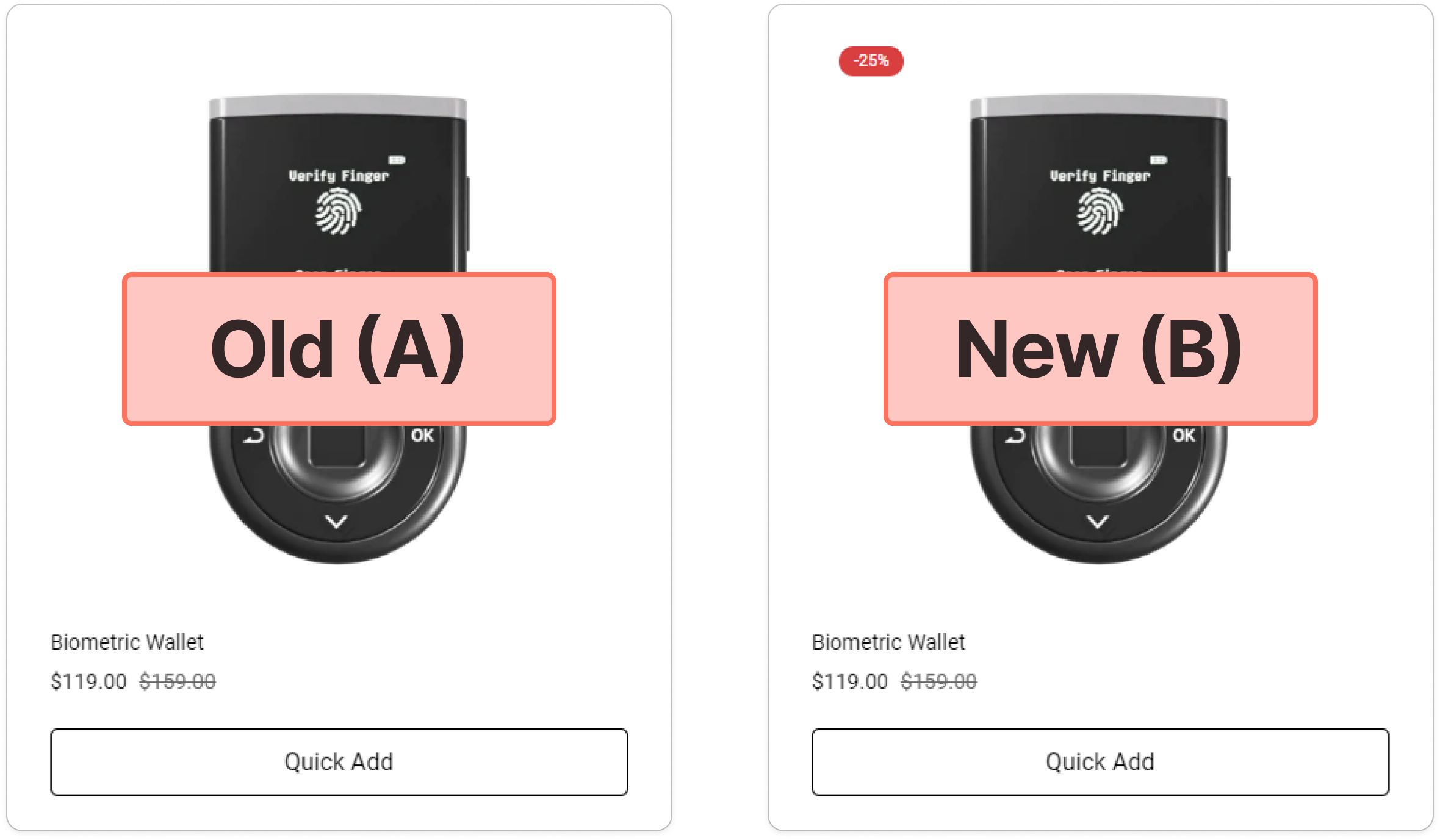

- A product manager suggested that displaying discount percentages (%) on product images could increase conversion rates by leveraging consumer psychology.

- We decided to experiment with displaying discount percentages (%) on product images to see its effect on conversion rates.

3.1. Proposal of the Experiment Idea

During a meeting to decide on an experiment idea, the product manager shared this suggestion:

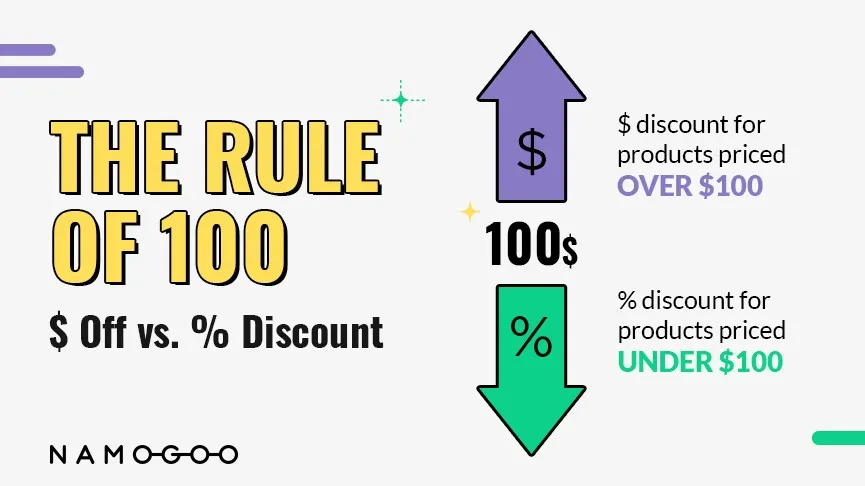

“We display discount prices ($) on product images. However, from a consumer psychology perspective, displaying discount percentages (%) might be more effective in certain cases. It’s worth experimenting with this.”

The idea was to highlight discounts and compare whether displaying percentages or dollar-off prices would be more effective in driving purchases.

Namogoo, an e-commerce SaaS platform, has discussed this further in their article on The Rule of 100, suggesting that depending on whether the price is above or below $100, either percent-off or dollar-off might be more effective. However, I believed this generalized rule needed testing in the context of our website.

3.2. Finalizing the Experiment Idea

We decided to test the following hypothesis:

“Displaying discount percentages (%) on product images might positively influence conversion rates.”

4. Actions

- Key metrics were set as the Purchase CVR and Average Revenue per User (ARPU), supplementary metrics were set as the Add to Cart CVR and Begin Checkout CVR, and the guardrail metric was the rate of users bouncing to other e-commerce platforms.

- We formulated the hypothesis that displaying discount percentages would increase Purchase CVR and ARPU, setting Type 1 Error (α) at 0.05.

- Using chi-squared tests, two-proportion z-tests, and two-sample t-tests, I validated the independence and differences between the test and control groups.

4.1. Selection of Metrics

4.1.1. Key Metrics

The core metrics selected were conversion rates and ARPU. Although having two key metrics can create ambiguity, I believed it was crucial to learn from multiple perspectives, given that the relationship between conversion rates and ARPU was unclear.

(1) Conversion Rate

- The final conversion rate of users visiting the experiment page

# Conditional probability based on total number of users

P(Final Purchase | Visit Experiment Page)

(2) Average Revenue Per User (ARPU)

- The expected average revenue per user visiting the experiment page

Total Revenue from Users Visiting Experiment Page ÷ Total Number of Users Visiting Experiment Page

4.1.2. Supplementary Metrics

In addition to the key metrics, I decided to measure the following two supplementary metrics. These metrics are closely tied to the core metrics and could provide valuable insights into adjusting the experimental direction or uncovering hidden meanings.

(1) Add to Cart Conversion Rate

- The rate at which users who visit the experiment page click the Add to Cart button

# Conditional probability based on total number of users

P(Click Add to Cart Button Click | Visit Experiment Page)

(2) Begin Checkout CVR

- The rate at which users who visit the experiment page click the Begin Checkout button

# Conditional probability based on total number of users

P(Click Begin Checkout Button | Visit Experiment Page)

4.1.3. Guardrail Metrics

Our company sells the same products on other platforms such as Amazon, Naver, and Coupang. However, the scope of the A/B Test TF’s activities was primarily limited to our own website’s conversion rates and ARPU. AlthoughI didn’t expect our website’s performance to negatively impact other e-commerce platforms, I set up guardrail metrics to ensure a holistic view of overall company performance.

(1) Rate of Switching to Other E-commerce Platforms

- The rate at which users who visit the experiment page click the button to visit other e-commerce platforms

# Conditional probability based on total number of users

P(Click on Link to Other E-commerce Platforms | Visit Experiment Page)

4.2. Hypothesis Formulation and Power Analysis

4.2.1. Hypothesis Formulation

Combining the experimental idea and key metrics determined during the meeting, we formulated the following hypothesis:

“Displaying discount percentages on product images will increase conversion rates and ARPU.”

The hypothesis can be expressed as the following null and alternative hypotheses:

| Key Metrics | Null Hypothesis (H0) | Alternative Hypothesis (H1) |

|---|---|---|

| Purchase CVR | The CVR of users visiting the existing page (A) ≥ The CVR of users visiting the new page (B) | The CVR of users visiting the existing page (A) < The CVR of users visiting the new page (B) |

| ARPU | The ARPU of users visiting the existing page (A) ≥ The ARPU of users visiting the new page (B) | The ARPU of users visiting the existing page (A) < The ARPU of users visiting the new page (B) |

4.2.2. Power Analysis

To establish the decision-making criteria for hypothesis testing, I conducted the following power analysis:

| Term | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Type 1 Error (α, Significance Level) | The probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is actually true | 0.05 |

| Type 2 Error (β) | The probability of failing to reject the alternative hypothesis when it is actually true | Not calculated |

| Power | 1 - β | Not calculated |

| Minimum Detectable Effect (MDE) | The smallest effect size required for practical action between the test group (A) and the control group (B) | Not calculated |

I did not explicitly define the Minimum Detectable Effect (MDE), as the entire deployment process for this experiment on the SaaS platform could be done easily with minimal development resources.

4.3. Determining the Analytical Methodology

The analytical process for hypothesis testing was designed as follows:

4.3.1. Independence Test

This test verifies the independence of the categorical variables between the test and control groups, ensuring that external factors were controlled before proceeding with the main hypothesis test. I checked whether the distribution of country and device type was independent of the group assignment.

- Country Distribution: Most visitors to our website are from South Korea and the U.S., so I categorized users into three groups: Korea, U.S., and other countries.

- Device Type Distribution: I categorized users into three groups: Desktop, Mobile, and Tablet.

(1) Test Statistic: chi-squared

(2) Hypothesis Formulation and Power Analysis

| Category | Null Hypothesis (H0) | Alternative Hypothesis (H1) |

|---|---|---|

| Country Distribution | The country distribution between the test and control groups is independent. | The country distribution between the test and control groups is not independent. |

| Device Type Distribution | The device type distribution between the test and control groups is independent. | The device type distribution between the test and control groups is not independent. |

| Category | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Type 1 Error (α, Significance Level) | The probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is actually true | 0.05 |

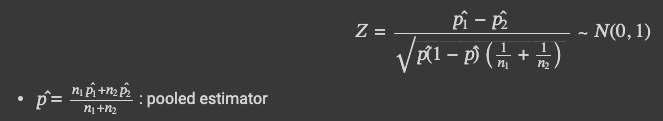

4.3.2. Two-proportion z-test

This test is used when comparing proportions between the test and control groups. I applied this test to the following metrics:

- Key Metric: Purchase CVR

- Supplementary Metrics: Add to Cart CVR, Begin Checkout CVR

- Guardrail Metric: Other Platforms CVR

(1) Assumption Check

- The number of conversions and non-conversions in both groups must exceed 5.

(2) Test Statistic: z

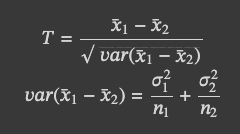

4.3.3. Two-sample t-test

This test is used when comparing numerical variables between the test and control groups. I applied this test to the following metric:

- Key Metric: ARPU

(1) Assumption Check

- The numerical variable in both groups must follow a normal distribution, or the total sample size across both groups must exceed 30.

(2) Bartlett’s Test for Equal Variances

- This test checks if the variances of the numerical variable in both groups are equal. It’s an important step before estimating the test statistic.

-

Hypothesis Formulation and Power Analysis

Category Null Hypothesis (H0) Alternative Hypothesis (H1) Equal Variance Test Variance of Test Group = Variance of Control Group Variance of Test Group ≠ Variance of Control Group Term Description Value Type 1 Error (α, Significance Level) The probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is actually true 0.05

(3) Test Statistic: t

4.4. Writing BigQuery Queries and Python Code

Data was retrieved from BigQuery and analyzed using Python.

5. Results

- Conclusion from key metrics: Displaying discount percentages did not bring significant changes to Purchase CVR and ARPU, which may be because it did not effectively communicate the inherent value of the product.

- Increase in Add to Cart CVRT: Discount information acted as a driver for purchase decisions, increasing the Add to Cart CVR, showing that visually highlighting discounts could positively influence user behavior.

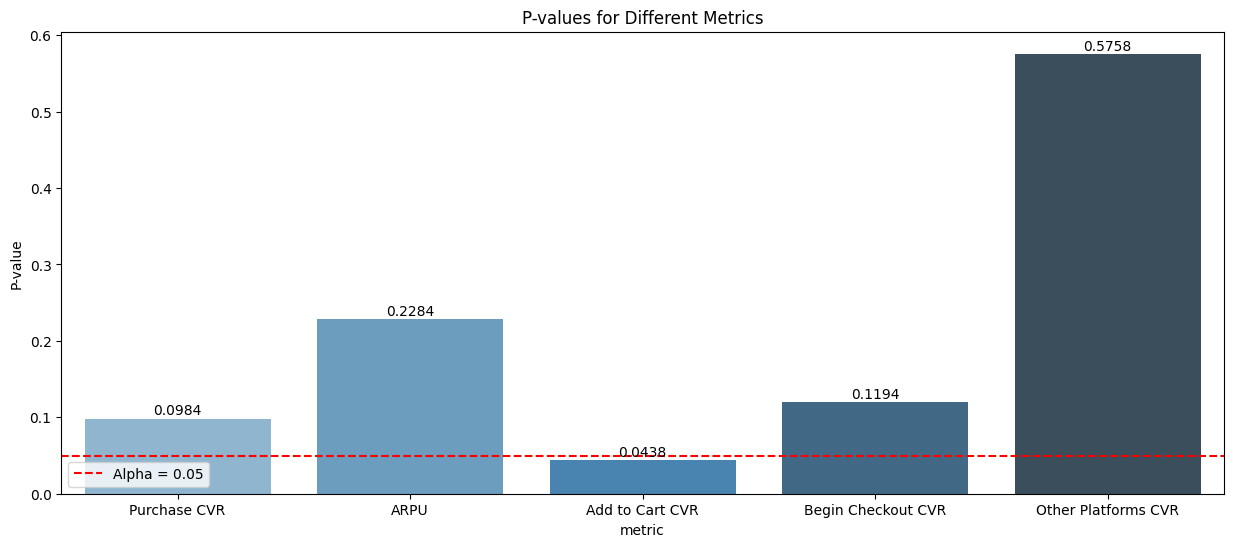

5.1. Analysis Results

| Type | Metric | p-value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key | Purchase CVR | 0.0984 |

A ≥ B |

| Key | ARPU | 0.2284 |

A ≥ B |

| Supplementary | Add to Cart CVR | 0.0438 |

A < B |

| Supplementary | Begin Checkout CVR | 0.1194 |

A ≥ B |

| Guardrail | Other Platforms CVR | 0.5758 |

A ≥ B |

5.2. Interpretation of Results

In this experiment, neither the key metrics of conversion rate nor ARPU showed statistically significant results that would allow us to reject the null hypothesis. In other words, there wasn’t enough evidence to support the alternative hypothesis. However, an interesting observation was made. The supplementary metric of the Add to Cart CVR showed a statistically significant difference, with the test group (B) outperforming the control group (A). Based on this, we can interpret the results as follows:

5.2.1. Importance of a Value Perception Strategy

It became clear that without a strategy to properly communicate the value of the product, it’s difficult to make significant changes in conversion rates or revenue. In particular, the method of displaying discount percentages in this experiment did not effectively highlight the inherent value of the product, which is why it failed to drive immediate sales. Our company’s products are high-value, protective items that require careful consideration, unlike common consumer goods that trigger impulse purchases. Therefore, a better A/B testing strategy might focus on more clearly communicating the unique value of the product or addressing customer concerns at the time of purchase.

5.2.2. Impact of Discount Information on Add to Cart Conversion

Although it didn’t directly boost revenue, the Add to Cart conversion rate yielded positive results. Discount information is perceived as a fleeting benefit that could disappear, encouraging customers to make faster purchasing decisions. While the discount percentage itself may not convey the core value of the product, it serves as an element that can indirectly influence the customer’s decision to expedite their purchase. This shows that visually emphasizing discounts can be effective in the customer journey.

Published by Joshua Kim